Greetings, Story366! Writing to you on this last day of June, which is in a lot of ways the halfway point of the Story366 project. After doing some math, tomorrow’s post will be the 183rd, so I’ll probably reflect more on the halfness of it tomorrow. Still, six months down, six to go. I look at all the book I have piled up on my shelf—at least sixty—and all the books I know I haven’t read yet, and I can’t believe there will a time in the not-too-distant future when I’ll not be running out of books, but of days. Does the end of 2016 mean the end of Story366, of story reviews? I don’t think so. I’ve realized, though, that I’m not going to review a selection every short story collection out there. That kind of kills me—note the collector persona I mentioned yesterday—but there’ll be more days to read and review after 2016 is over.

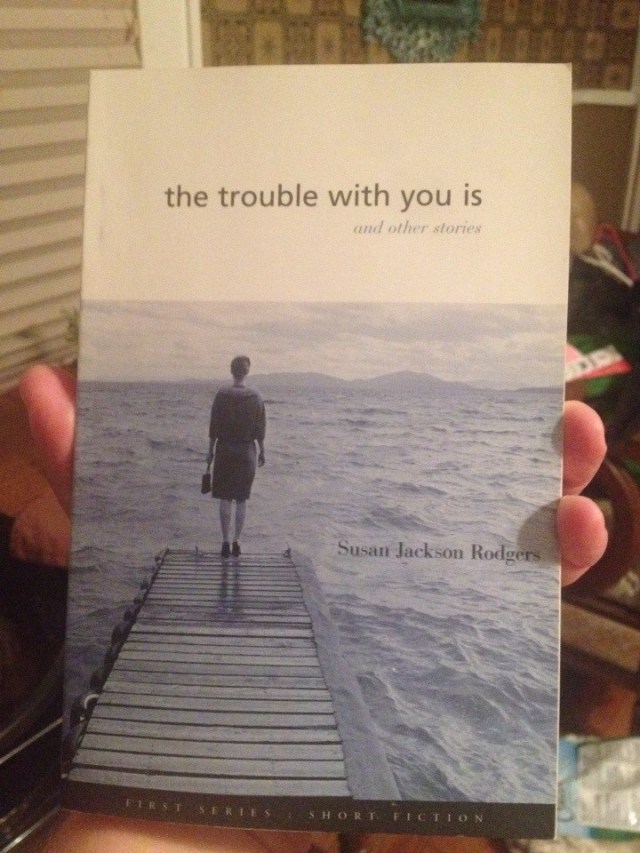

Today I’m writing about Susan Jackson Rodgers’ collection The Trouble With You Is, out from Mid-List Press as a winner of one of their First Series Award winners in fiction. I haven’t done a Mid-List Press book yet this year, and picking up Rodgers’ book made me think of an occasion when I met the press’ founders and editors. It was 2004 and I was on a panel of editors in Washington D.C., in the basement of one of the Smithsonian Museums, for a packed Saturday morning panel. I’m not sure what the event was, or if there even was an event, but I drove out from Bowling Green, stayed in some hotel off the Mall, did this panel, then basically drove home. I was gone less than forty-eight hours (though those forty-eight were during cherry blossom time, so that was cool).

Lots of things about that trip, remembering it now, make me kind of sad and nostalgic. Firstly, I can’t remember the names of that couple I sat on the panel with, the Mid-List Press people, even though they were very sweet to me. They were in their sixties, I believe, had been married for over forty years, and hung out with me after, taking me to lunch and to the art museum across the Mall. We talked about publishing and they explained what Mid-List was, how they got their name. Here goes: Mid-list titles, according to them, are the best titles in a press’ catalogue. There’s the front list, meaning the new titles, and the backlist, meaning the standards, the books that keep the press alive, things like dictionaries and The Illiad and The Odyssey, titles a press doesn’t have to deal with much but sell tons of copies nevertheless. The mid-list, however is comprised of the books the press really loves, the special projects, those literary titles that aren’t new and don’t sell all that much, but are the editors’ favorites. They wanted every book to be a mid-list book. It sounded good to me, especially since that was before I had a book out and was entering all the collection contests (with what would become Elephants in Our Bedroom) with no luck. One year, I had to have lost to Rodgers and The Trouble With You Is, which makes sense, as this is a really nice collection, certainly better than what I circulating in 2014 (Elephants was accepted in late 2007 and was released in early 2009). But those were nice people, and researching Mid-List Press just now, I couldn’t find any founders’ names or any names on their website; the press has moved from Minneapolis to Nashville, and they haven’t run the First Series Awards in quite some time. They still take queries, so maybe they will make books again.

Rodgers’ collection seems to be dealing with lost, troubled souls, and maybe that’s what the title means, that everyone—at least all of Rodgers’ protagonists—have trouble, or are trouble.I read a few of the stories to write this entry, including “The Trouble With You Is,” the title coming from the protagonist’s boyfriend, who likes to start sentences—unfortunately aimed at the protagonist—with that phrase. Not an encouraging way to start a conversation. I like that story, about this lost woman who follow boyfriends around the Midwest, around town, simply because she doesn’t have a plan, as in no life plan at all. It’s a solid story, but I liked one I read a bit better: “Bust.”

“Bust” is about Nora, a thirty-five-year-old two-time divorcee who has breast cancer and is about to have a double mastectomy. Nora has never had large or in any other way enviable breasts—it had been a sore subject most of her life—but now that she’s about to lose them, she doesn’t want to forget them. She has a friend who is dating a sculptor and somehow the idea pops into Nora’s head to have this sculptor cast her, make a molding of her chest, then turn that into a statue, a piece of art to commemorate her soon-to-be removed parts. Nora goes to the sculptor’s apartment and finds the sculptor—Deirdre—to be an energetic, larger-than-life personality, if not a little enigmatic. After a brief chat, Deirdre is ready to get on with it and has Nora, shy, shy Nora, strip off her top so they can get started, right there in her apartment. To ease Nora’s qualms, Deirdre whips off her shirt and bra as well, and ironically, Deirdre has large, round, perfect breasts. Still, Nora relents and within seconds Deirdre is smearing her with Vaseline and plaster, her hands all over her, in the most professional way. Nora is going to have her cast, her bust, and that makes her feel a little better about her situation.

Nora has the surgery, which is successful, though followed up by radiation. Weeks turn into months without Nora thinking of Deirdre or her sculpture, not until Deirdre sends her a postcard notice about a show opening in a chic Manhattan gallery. Nora doesn’t want to see a show—she just wants the bust of her now-removed breasts, the piece she commissioned. Only there’s a trick: The gallery doesn’t want to give it to her. The gallery isn’t a storage facility and it isn’t a pick-up window for art. Nora’s bust is in a show, the first piece in a series of naked torsos that Deirdre has assembled. Nora thinks about grabbing her bust and running, but the gallery curator makes it clear that if Nora doesn’t leave, he’ll call the cops. Nora instead seeks out Deirdre, whose been avoiding her, and it’s soon obvious as to why.

That’s as far as I’ll go with the plot. As you might guess, Nora runs into more trouble trying to procure her sculpture, especially when confronting Deirdre herself. The ending the story is really perfect, taking this narrative—at its core, remember this is a breast cancer story—in an unexpected and satisfying direction. This is a great story.

Thematically, though, is how “Bust” really shines. Poor Nora, whose own mother died from breast cancer, is trying to survive this disease, and splurges both emotionally and economically on this sculpture, hoping for a small victory. Like with her actual breasts, she finds out she can’t have it. The parallels to the cancer are pretty obvious, that Nora is again having her breasts taken from her by an uncompromising force. Nora simply won’t go down without a fight, not to the disease, not to some snobby museum employee, not to the woman whom she’s trusted so intimately, a woman who’s betraying her on so many levels. I kept thinking: Wait, you need to get something for letting that woman violate you! And that’s really only one part of it all.

Susan Jackson Rodgers has a way with people when they’re at their most desperate, the absolute best time to write about them, one of the bullet points on my “How to Write Stories” handout (I’m not making this up—this actually exists). I enjoyed reading Rodgers’ stories from The Trouble With You Is. Good stuff.