Happy Thursday to you, Story366! The heat has returned to Southwest Missouri, along with a lot of other places, so I’m happy to be traveling later today, in the AC, as opposed to splitting timbers or tarring a roof or something like that. I will soon be en route to Chicago, where I’ll catch a few games at Wrigley, slinging suds up and down the aisles and making up for my the eight hours on my ass in the AC. I’ve only vended beer at six games so far this year and none in over a month, so I’m pretty eager to see what else they’ve done to Wrigley Field and the surrounding neighborhood—there’d been quite a few changes over the winter—as I’m half-expecting a new skyscraper in left field or a racetrack around the park, something of that order. Not that I’m into racing—of any kind—but I am amused by the thought, people or horses or dragsters circling the stadium during the game, some spectacle to add to the carnival atmosphere. Maybe they could have peacocks race iguanas, something interesting like that. More than likely, another fancy bar with overpriced burgers and craft beers will have shown up instead, as if these people need to drink $13 Blue Moons outside the park when they could be pre-gaming inside instead, buying a $10.50 312 from me.

Speaking of my vending gig, the world went ahead and did it: The Surpreme Court made the world even shittier yesterday by sticking it to unions—we beer vendors are unionized (it’s Chicago, so of course we are). This on top of the fact that one of the nine—the sensible right guy—has announced his retirement, meaning someone like Jeff Sessions or Voldemort will be nominated promptly. When I said on Tuesday that I didn’t think I’d be writing about politics for a third entry in a row, I honestly thought these knobs would take a day off from the awful and I could talk more about the weather, but like so many times this past couple of years, I was proven incorrect. So, there you go.

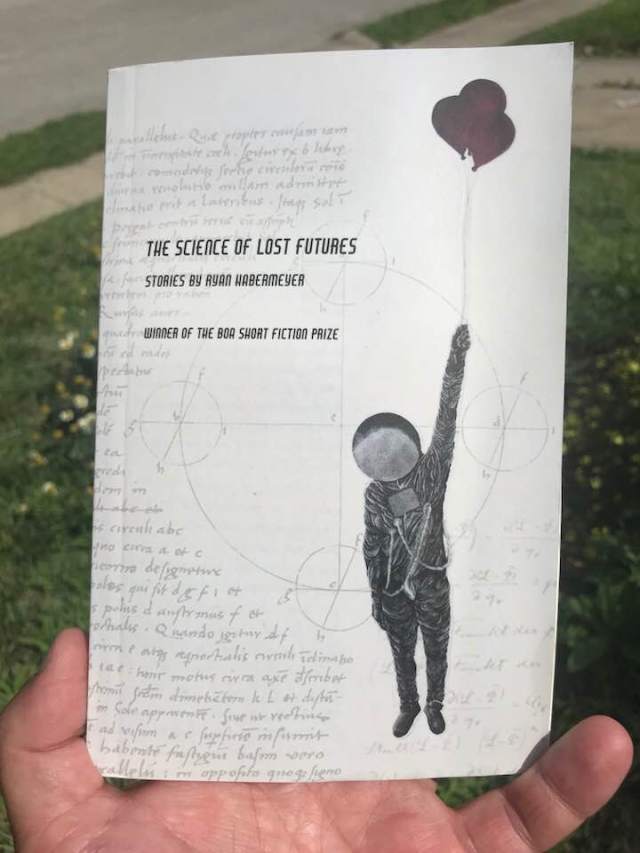

For today’s entry, I read from Ryan Habermeyer‘s 2018 collection The Science of Lost Futures, winner of the BOA Short Fiction Prize from BOA, and it’s a book I’m somewhat familiar with. A couple of years ago, this book was a finalist in the Moon City Short Fiction Award, so I’d read at least a part of it, though if memory serves me correctly, Habermeyer pulled the book before we finished the judging, as he’d won this BOA award. We couldn’t be happier for him, as we took an extremely awesome book (I think that was the Michelle Ross-There’s So Much They Haven’t Told You year) and Habermeyer ended up on a really awesome, reputable press in BOA. Everybody wins (or at least Ross and Habermeyer, anyway).

Not sure if I’ve ever made this pronouncement before, but this may be the book that I had the hardest time in picking the story to write about. I read four of the stories in The Science of Lost Futures and I loved all of them, firstly, but all of them are also quite unique, completely different stories in style and theme from one another. The first story I read is the opener, “A Cosmonaut’s Guide to Microgravitic Reproduction,” about this regular Joe who signs up for the Cosmonaut program, goes through rigorous training, only to find that he’s being shot into space with a woman to test for the sexual positions that are most reproductive in zero gravity. Habermeyer has fun with this, as the dude’s log reads like a zero-G Kama Sutra, the whole thing absurd, yet the author makes it strangely moving. The third story in the book, “Visitation,” is about this guy whose wife’s womb falls out, then just kind of hangs around, sort of like if a hot water bottle was a houseguest. I flipped ahead a bit to get to “Indulgences,” in which the protagonist works at a doll factory, in quality control, where every fifty seconds or so, he’s got to strip naked on the assembly line and let the dolls—who have all kind of sensitivities and abilities—stare at him. He doesn’t know why he has to be naked or what comes of it, but nearly six hundred times a day, a piece of robotic plastic gets to eye his junk. And then there’s just a bunch of stories I want to read based on their titles alone, pieces like “Frustrations of a Coyote” and “A Genealogical Approach to My Father’s Ass.” I mean, what’re those about? I’m going to find out.

Still, I had to pick one, so I picked “The Foot,” the second story in the collection, one that I think is just perfect. In this story, there’s an unnamed, and for the most part, undescribed village, and one day, a giant foot washes ashore. The foot is as big as the town’s biggest water tower, and because it’s been in the sea for God knows how long, it’s covered in seaweed and barnacles and is pale and bloated like, well, a whole person would be if they washed up on a seashore. The story, told (mostly) in first plural, ventures on describing what happens afterward, and like any good communal narrator story, it reveals the reaction of the entire town, what some people think about this, what others think about that. There’s all kinds of theories about where the foot came from and what it means, and eventually, someone wonders where the rest of the person is that this foot belongs to; my favorite line is when one woman tells the crowd to call her when the cock washes up. There’s a lot of humor in this story, some of it tongue in cheek, the rest of it unnecessary to hide in that manner. This is a funny story, because of course it is: A giant foot has washed up on a beach.

Habermeyer takes us through the town’s stages of reaction, from shock and awe, to curious, to weird, to a whole bunch else. Scientists eventually show up and do all sorts of tests, while at the same time, the people of the town clean and care for the giant foot. Children eventually use it as a playground; teenagers use it as a makeout point. The foot becomes part of the town, an odd fixture like a sinkhole or tire fire, becoming as much a part of the community as anything. One particularly touching passage involves the possible identification of the foot, someone remembering an old folk tale about an orphaned girl named Ada who disappeared, who once said something about feet before she vanished. It’s a passage that comes out of nowhere, writing that gives real depth to this story, proving it’s not quite as light as I’ve perhaps made it out to be.

I won’t go any further into what happens next, but even at this point, I’m sure a lot of you might recognize this somewhat, as it’s strikingly familiar to Gabriel García Màrquez’s classic “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World,” which is one of my favorite stories of all time. In that story, a giant man—maybe like a dozen feet tall—washes up on the shores of this tiny Columbian village and before long, the villagers are cleaning him, dressing him, calling him Esteban, and well, you can read that story, too. I’m pretty sure someone with Habermeyer’s pedigree (all kinds of degrees and publications) has read this story and had García Màrquez’s tale in mind when he wrote it. Habermeyer’s story is not a rewriting, I don’t think, but it’s certainly homage, and a fine one at that, worthy of being named alongside that perfect piece of literature.

I could have written about any of the stories I read in The Science of Lost Futures, as all of the stores were not only a lot of fun, but they worked, as they say, on a lot of levels. Ryan Habermeyer instills depth within his protagonists, surprises just when you think you’ve figured his stories out, and wit that you really can’t learn. This is one of my favorite collections I’ve read this year, but also for this entire project, each piece speaking to me as a reader and a writer. What a talent, what a collection.