Happy Friday to you, Story366!

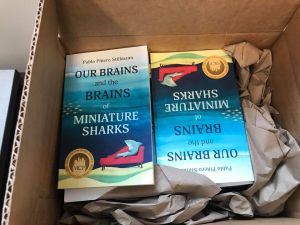

Today, a lot of the work I’ve done for Moon City Press came to fruition as our two newest titles were shipped. Take a gander:

Both titles are existing on soft-release status until after the AWP Conference, as we just didn’t get them done in time to stock up at the distributor and do a proper release before leaving for San Antonio. Look for me to blast info about ordering both titles—Moon City Review 2020 and Our Brains and the Brains of Miniature Sharks by Pablo Piñero Stillmann—soon after the conference.

To note, when we’re in production mode and I’m working on these titles—as I’d been since the beginning of the year—I’m always a bit stressed out. I never really sleep that soundly, as I worry about the books being perfect. The fact we waited almost until the very end to have them finished in time didn’t help. Worse,, the week between ordering the books and having them delivered is particularly a grind, as I’m worried about them looking good, that I’ve just ordered a botched titl. No matter how many times we check the book before submission—and that’s after major edits, revisions, and a standard galleying process—and no matter how long I stare at the proofs from the printer, I somehow think the books will come back all screwed up. Maybe there’s a page missing and the odd-numbered pages will show up on the left side. Maybe the cover art won’t reproduce too well. Maybe I’ll misspell the author’s name on the spine. Maybe there won’t be a page 44 and no one will understand what the hell is going on. You know, mistakes that would negate the entire print run, cost the press thousands of dollars, and make me look like an idiot hack dumbass.

Luckily, none of that happened and the books look super-awesome. I’m stoked about that, glad for our authors, particularly Pablo. And I hope to sleep well tonight. I have a feeling I will.

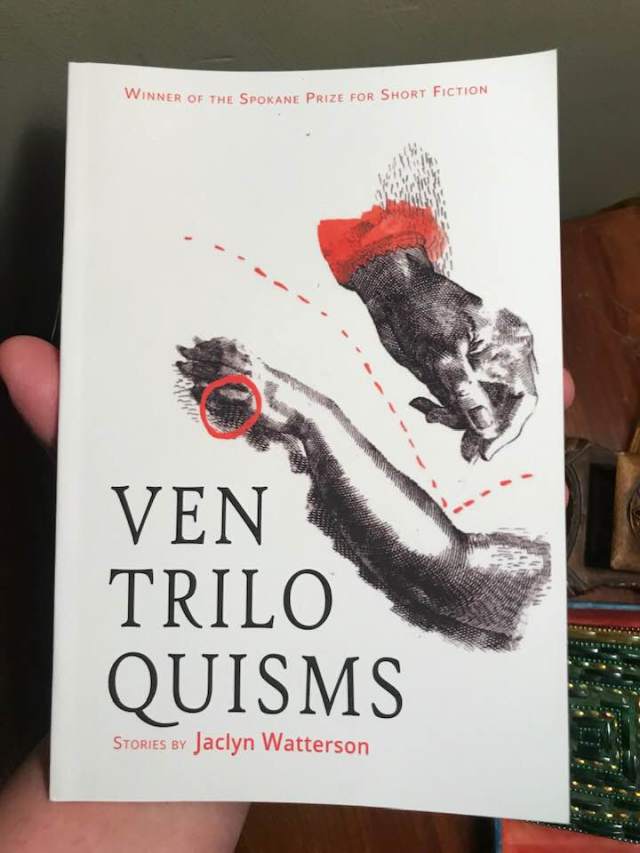

For today, I read from Jaclyn Watterson‘s 2017 collection Ventriloquisms, out from Willow Springs Books as the winner of The Spokane Prize for Short Fiction. I’d not read anything by Watterson before tonight, despite prolific publishing in lit mags, so I was, as always, excited to dive in and see what was up.

Ventriloquisms is a book of shorts, so I read the whole thing tonight. There’s a multitude of stories I could have focused on in this entry, stories that stood out to me, stories I’ll remember. I really love “A Baby Is a Dreadful Thing,” my second choice to write on today, about a woman who’s trying not to turn into a baby, like all the women in her society are doing. “Pinchbelly” is sort of a nursery rhyme, or at least reads like one, at least of the tragic variety. “Some of Us Had Been Sucking Our Friend Carrie” tells of a group of women literally consuming their friend—lots of nice, twisted description in this one. “My Laxative” is about a woman who is more or less dating a man who is also a laxative, ordered online and delivered to her house. “Apology for My Brother” is a crude kind of discovery between a brother and sister, exploring genitals and identity and whathaveyou. So, lots of good, strange stories here, but really, I liked something about most of the pieces in the book, to varying degrees.

Tonight, though, I’m focusing on one of the longer stories, “Charlie’s Kidney,” a story that has more of a plot and traditional arc. Maybe I chose it because of that, because subconsciously, I knew it’d be a little easier to write about—or at least not reveal the entire story in one paragraph of description.

“Charlie’s Kidney” presents to us a world where everyone is freezing and the frozen are being distributed as meat. In the meantime, we’re also introduced to Charlie Habsburg, the guy every girl wants to marry, from whom every girl wants affection and favor. Our protagonist and narrator, Maria, is among those women, and she sets out to win Charlie’s eye, to become his bride.

Maria sets out to win Charlie with a curtsy, which doesn’t work, and also puts on a wolf costume she bought at a department store, which doesn’t work, either. In the meantime, Maria’s older sister, Baby Grace, is also trying to woo Charlie, as are several other women in this world. There’s an interesting, fun scene where the women all line up and get to ask Charlie a favor—he’s rich, by the way, and in need of an heir—and Maria takes her sister’s advice and asks for a kidney. That’s about when the curtsy doesn’t win her any favor, and shortly after, when she auditions the wolf costume.

If it seems like I’m not making too much sense in summarizing this story, it’s because I’m not. Watterson’s worlds are often metaphorical, absurd, and dreamlike, which she’s really good at relaying in her stories, via her prose, the progression of the narrative, and the simple expecation of what she’s doing after you read two or three of the stories. Me, when I’m trying to sum up? I’m bad at it.

Anyway, the story recounts more of the courtship era, several women doing this and that to become Mrs. Habsburg. It’s not unlike an episode of The Bachelor, I would guess, never having seen the show, but understanding the concept. Charlie seems just as fickle as a guy would have to be on a game show, women doing all kinds of crazy things to become the one, wearing monster outfits and asking for organs and whatnot. I loved that about the story, that there was a plot here, a motivation, but that didn’t make Watterson follow any rules, fulfill our expectations of story, or dot any of her small Js.

Remember that part about the world being frozen and the living eating the dead? Have I mentioned that I think Charlie might be dead for part of this and the women are fighting over his organs, wanting to eat him instead of marry him? No?

Eventually, Charlie does make a choice, which I won’t reveal. Probably my favorite part of this, however, is that Maria ends up with three kidneys—yeah, she just puts the other one inside her. Maria notes, “You may say three kidneys is too many, and I say, Two were not enough.” Watterson won me over totally and completely at that point because damnit, she’s right: If two kidneys work so well, why wouldn’t three be better?

That’s the kind of logic and grace and irreverence I found in Ventriloquisms, Jaclyn Watterson’s debut collection of weird and wonderful shorts. I never knew what to expect when I started any story, nor did I know where or how any particular piece would end. Watterson really pushes the definition of what story is and can be, reminding me of the best works of Lydia Davis and Amelia Gray, two authors I’m quite fond of. This was the perfect book for a Friday night, after a long, triumphant week. So glad to have picked it up tonight.