Monday again, Story366!

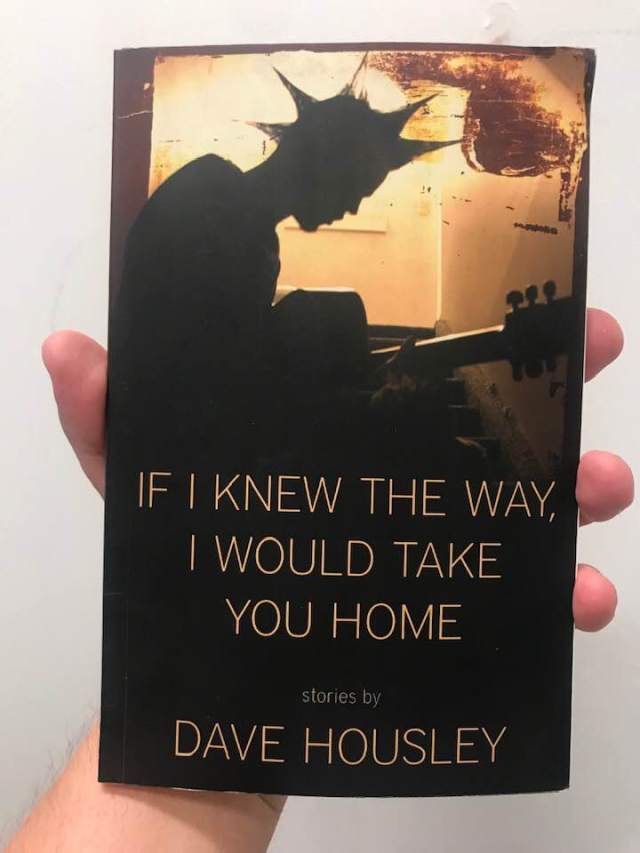

Today I continue with my week of posting on an author for a second time, meaning I already covered them once, but have a different/new book by them and am doing that book now instead. That doesn’t really roll off the tongue, not like Sweeps Week or Taco Tuesday. Two-Timers Week? Sure. Let’s call this Two-Timers Week.

Dave Housley yesterday started us off and Melissa Pritchard is second today with The Odditorium, out in 2012 from Bellevue Literary Press. I originally covered Pritchard in June of 2016, reading from her Disappearing Ingenue: The Misadventures of Eleanor Stoddard (and a story about the Brach heiress murder, if I’m not mistaken). I remember writing that entry in a Drury Inn in Collinsville, Illinois, on the way to a trip to Chicago, my family down at the pool as I pecked away at the desk. I loved that book and love The Odditorium as much, maybe even more.

The Odditorium, as the title might indicate, is filled with stories about the unconventional, misfits who have a place in this world, even if that place is not having a place. The lead story, “Pelagia, Old Fool,” is a romp about this mid-nineteenth-century Russian woman who goes from unwilling bride to outcast to nunnery convict to saint over the course of various circumstantial and incredible adventures. It’s a riot, really, one that includes some tragedy, too. Bonus points to Pritchard for following Pelagia throughout her whole life, and beyond, through Russian history, all the way to Gorbachev. There’s even an epilogue, of sorts, at the end, called “Three Morals,” three random anecdotes/vignettes that I liked, too.

I next read “Ecorché: Flayed Man,” which is switching-POV story, told from three different perpsectives, thethree links on the chain of what happens to a body, in Florence, Italy, in 1798. First there’s the Collector, who finds the bodies, then the Director, who does the dissection and research on the body, and finally, the Anatomist, who prepared the body for display and final rest. The story starts by following this chain as it deals with the corpse of a beautiful young woman, incidents that lead us to see our three protagonists display some rather lewd and disgusting behavior. The story moves beyond the girl, eventually, focusing on these three sad little men more as individuals. Again, after, Pritchard adds a three-part epilogue made of vignettes. Makes me think she likes doing that, adding trios of little stories onto the main story.

I’m focusing on the title story today, “The Odditorium,” which is basically a first-person, primary-resource account of Robert Ripley, of Ripley’s Believe It … or Not! fame. Part of it seems like literary biography, which I liked. I used to read those Ripley books when I was a kid and liked the TV show with creepy, pre-Oscar Jack Palance as the host. So, I liked the facts of Ripley’s life, like how he was funded by William Randolph Hearth. That he was a womanizer, but only married once, for less than nine months. Or that he traveled around the world, himself, decked out in a pith helmet and safari gear, looking for his treasures. Best of all? His swimsuit also included a pith helmet. Now I kind of want to read a full-length biography about this guy.

The story also focuses on a character that’s often referred to as The Appendage, one Norbert Pearlroth, who served as Ripley’s researcher. As dedicated and anal as Ripley was about finding artifacts, Pearlroth proved just as thorough, spending thousands upon thousands of hours in the New York Public Library, making sure every stunning fact was accurate, every unreal claim true, every preposterous boast legitimate. This went on for over forty years. And the weird thing? He and Ripley never met.

That’s really most of the story, except there’s a semi-revelation at the end, that the narrator of this story is Pearlroth himself, and I say “semi” because I kind of knew that the whole time. But I think that’s part of the narrator’s voice, his character, to end the story with that flourish—I think Pritchard knows we know, but is letting poor Norbert have a moment.

As this is a first-peripheral story, with an out-of-body add-on thrown in, I get a Nick/Gatsby vibe here, that Pearlroth admires Ripley, especially at the story, but there’s also some underlying frustration, even some jealousy. Ripley got to be the face of the venture, the celebrity, while Pearlroth had his books. Maybe I’m misreading that, but maybe not.

Before I conclude, I have to note that Prithcard is an absolute master at sentences. I don’t quote texts here very often, but check out this line from “Pelagia, Old Fool”:

Father Seraphim, many years dead and a venerated saint, arrived to administer the sacraments, and Anna claimed to have seen with her own eyes an angelic being descend through the roof, whisk Pelagi off in its alien arms, and return her, babbling incoherent, at dawn.

And that’s just one example: Most of the story is made up of sentences of that complexity and structure, adding to the absolute joy of reading this piece.

Again, I can’t believe I put off reading this book for so long simply because I’d already read one of Melissa Pritchard’s books. The Odditorium is a beautifully weird collection, chock full of Pritchard’s master over the English language and uncanny ability to spot and peg an oddball. This is a book I want to eat up, reading it so fast, so hard, that it’s like I never avoided it for so long, so stupidly. What a fantastic writer Pritchard is, and what a book she’s given us.