I’m pretty sure today is Friday, but I’m not 100%. Really, I just had to look at a calendar to find out the day of the week: That’s how blissful this break time has been. Reading, writing, cooking, eating, and having massive Nerf gun battles with my boys. I know that I’m supposed to do stuff to make money, but, you know, if I could sustain my life—pay my bills, eat, travel, etc.—and not work? I would do that in a heartbeat.

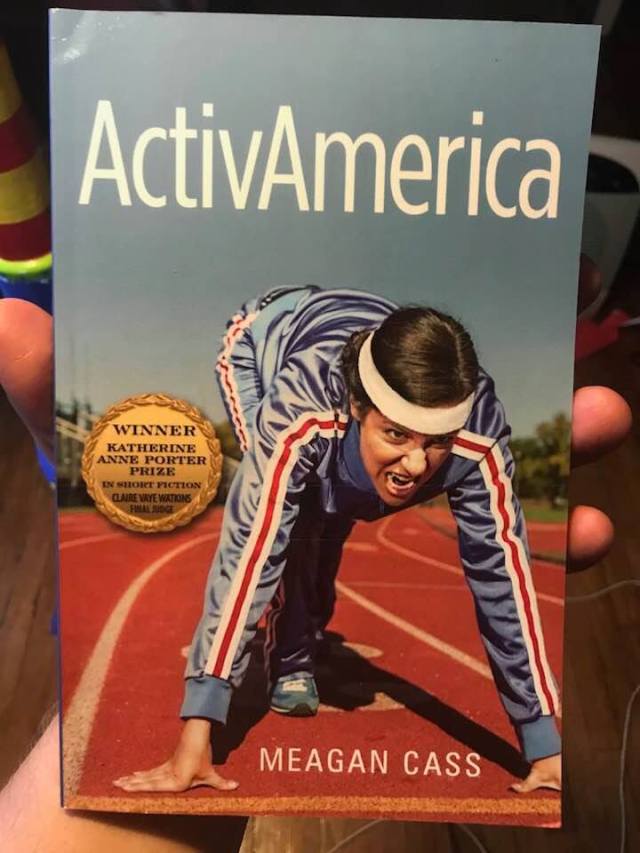

Today is the … third? … day in a row that I’ve done a post and I’m really enjoying these new books. For one, it’s a relief to read something that’s not on 8.5 x 11″ white paper, things that need to write on with a pen. Maybe I’m still relaying wisdom and commentary for these posts, but at least it’s a change of pace: It’s not like Samantha Hunt or Meagan Cass are going to go back to their stories and revise because of anything I’ve said. That takes a little pressure off me. Plus, that white paper. Ugh.

Secondly, three books in three days have produced perhaps the three most different books I’ve read in any stretch, as Hunt and Cass’s books had their own particular aesthetics (described in those posts), and today’s focus, Wayne Harrison, is no different. Hunt’s stories are elegant masterpieces, all over the place in terms of perspective and theme. Cass’s ceaseless imagination make for an eclectic and fun ride. Harrison, however, is more of a callback to previous styles, more traditional stories in both telling and structuring. I won’t go so far to compare his work to Carver’s (which is so easy to do), but certainly, I thought of Carver’s direct contemporaries here, Tobias Wolff and especially Larry Brown. In any case, Harrison writes a solid, mean-ass story.

I read a few stories from Harrison’s Wrench, the most recent winner of the New American Fiction Prize from New American Press. Since they were all solid, I could have written about any of them, and almost wrote about the title story, “Wrench,” though I’m going with the lead story instead. “Least Resistance” is a piece that back in the day was in The Atlantic and Best American Short Stories. I’m not sure if Harrison is “known” for a story, but if he was, this would probably be it, right? (And note, I’m pointing this out because I wish I was “known” for a story, for something as high profile as “Least Resistance” has perhaps been for Harrison.)

“Least Resistance” is the story of Justin, an almost-nineteen mechanic working in the garage of a regionally, and possibly nationally, famous hotrod guru, Nick Campbell. Nick inherited the business from an uncle some years back and moved with his wife, Mary Ann, from Oregon to take over. Magazines write stories about Nick’s prowess and middle-aged tough guys come in with their Iroc-Zs and Chargers to have Nick install upgrades, thousands of dollars to get a sweeter-sounding engine or a few more MPH. Justin admires the heck out of Nick, workships him, in fact, and is becoming his star pupil, leaping over Sammy, an older, more temperamental, and simpler guy.

Good setup for a story—don’t read too many set in garages (more on that soon)—but Harrison immediately complicates matters by the end of page two when he reveals that Justin has been carrying on with Mary Ann on his off days, fornicating on the living room sofa when they know Nick can’t leave the garage. Mary Ann, the older, wiser, and forbidden lover, has Justin smitten, despite some serious rules, like only doing it missionary-style and Justin never, ever entering Nick and Mary Ann’s bedroom. Still, Justin gets to spend his days frolicking with his boss’s wife, staying naked for hours on end, because, well, they’re going to keep going at it and clothes would only get in the way. For an eighteen year old, one apparently without scruples, it’s a fantasy come true.

Does Justin’s infidelity with his idol’s wife have anything to do with Nick’s recent fuck-ups? As of late, Nick has had a lot of rechecks come in, meaning those custom jobs guys pay him a lot of money to execute are pulling back into the garage, something pinging here, something leaking there. To me, who can change a tire and that’s about it, that doesn’t seem like a big deal, but to these gear heads, Nick might as well have pissed in their cup holders. Soon, Nick’s reputation goes from go-to to nil, putting this business, livelihood, and marriage in jeopardy. The tension just gets thicker when Nick calls Justin, asking him about another botched job, and Justin is literally on top of his wife. Because this is a story, something’s got to give, right?

There’s more complications to come before any dam breaks, before we reach any sort of climax or resolution. I won’t reveal any of that here, though, as I want to leave something for you to discover. I will point out, however, that Harrison really sells the mechanic stuff, listing endless adjustments, ailments, and conditions that make it seem like a real mechanic is telling the story—and for good reason, because Harrison worked as a mechanic for five years before settling into life as a writer and professor (with a stop-off as a prison guard in between). One writing rule I have is never try to write from a military POV, as there’s no way that I, who has never served, could ever convince anyone I knew what I was talking about—veterans can smell and civilian poser a million miles away. The same could be said for mechanic stories. Maybe that’s what reminds me of Larry Brown, a fireman-turned-writer, his authentic-sounding fireman stories. That’s why I focus on middle-aged dorks in my fiction: Air-tight legitimacy. I got the street cred dripping off me, left and right.

Three stories into Wrench, I’m a fan of Wayne Harrison’s work, solid tales about working-class dudes trying to make their way … despite the fact they try their hardest to fuck things up. Harrison’s stories are about people earnestly trying to change, and from what I’ve seen, they do, in some ways, as trying hard will often get a result. These stories are existential in that way, Harrison’s protagonists sincere but limited, victims of their own choices, their own limitations, but also of the choices others make, of their predicaments. I found myself rooting for these heroes, wanting them to win out, but by the third story, had the distinct feeling they wouldn’t. That’s the world Harrison writes about, a world that’s a helluva place to visit, especially when led by such a talented guide.