Hey hey, Story366!

Today is another beautiful, sunny day in Springfield. And it couldn’t come soon enough. Last night, after doing some work and putzing around, I wandered up to bed around two a.m. At 3:12 a.m., I jolted awake from an anxiety dream, some simple combination of me being stuck somewhere/me not being able to do something, which for me is sort of a mental claustrophobia. Usually, I can get up, turn on a light or two, get a drink, and regain my bearings. This morning, however, I couldn’t shake the feeling. When I tried going back to bed again, five minutes after I woke, I almost immediately felt trapped, enveloped by my bed, the blankets, the sheets and pillows, and most of all, the darkness.

I jumped up again. This time, the Karen woke, too, and worked with me. She followed me downstairs, rubbed my shoulders, said sweet things. After ten minutes of this, I tried one more time to get into bed, but nope. I again felt the overwhelmingness of our situation, of the night combined with the quarantine: I wanted it all to be over, both night and our inability to do what we wanted. Rationally, I knew both things would end in time—darkness in a couple of hours and quarantine in a month or two. But when I become anxious like this, feel the mental claustrophobia, rationality doesn’t apply.

Karen, who usually gets up around four on Tuesdays—her paper’s production day—was happy to sit with me in the wide-open living room/kitchen area, help coax me out of it. We put on shoes and stood on the back deck, in the cold and rain; we talked about nonsensical whimsy; we watched a couple of episodes of 30 Rock, which we’ve been rebinging the last week; she rubbed my back some more and we tried to fall asleep on the couch.

At five, her alarm went off and it was time for her to get to work—she usually has a dozen stories to write every Tuesday, little local paper snippets that she’s researched, conducted interviews for, and taken notes on during the previous week. I was more than happy to occupy myself and my thoughts, to make Karen her breakfast, to pack her a lunch. By the time I was done with that, the sun started to peek out from eastward and I felt better. I sat down on the couch and nodded off. Around six-thirty, Karen suggested I try the bed again, so I went up and immediately fell asleep, not waking until just before eleven, and only because the boys were up and wanting breakfast.

So, that was my early morning: a panic attack. I feel fine now. I’ve cleaned up around the house, read, took a shower, and got the boys outside to rake up the deck. Now we’re sitting at the table, me writing this post, them attempting at-home schooling.

How are you?

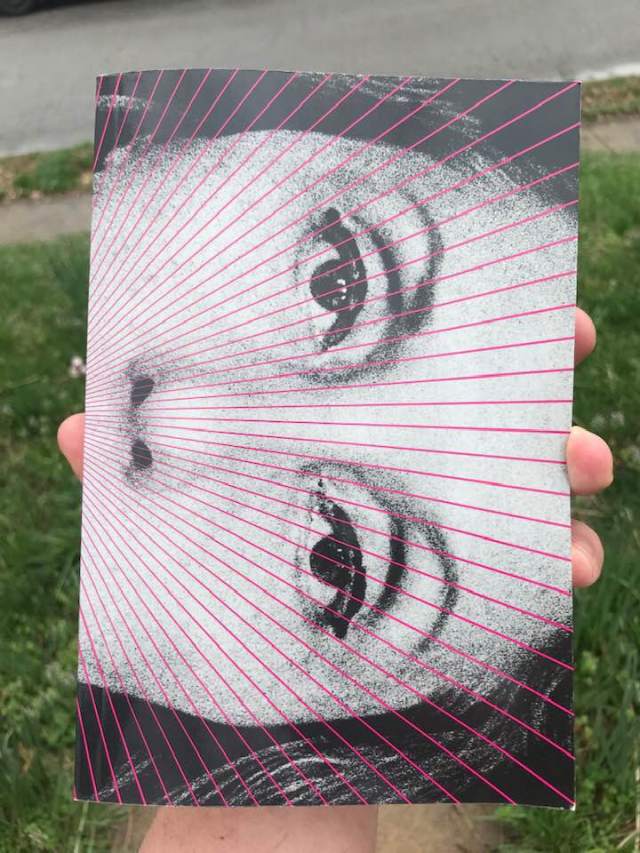

That book I read from today was The Empty House by Nathan Oates, out in 2013 from Lost Horse Press/Willow Springs Books as winner of the 2012 Spokane Prize for Short Fiction. I’m familiar with Oates’ work—he was a runner-up in last year’s Moon City Short Fiction Award—but I’d not read any of these stories from The Empty House, his first book, despite them appearing in a lot of magazines and anthologies. So, here we go.

Oates’ collection basically deals with people travelling abroad, sort of the like other collections I’ve covered this year, including Derek Green and Serena Crawford. While Green’s book is about people working abroad and trying to profit from those situations, and Crawford’s is about lost people trying to find themselves, Oates’ stories lie somewhere in-between, as his travelers are sometimes lost when they embark on their journeys, but also become lost—or worse—while on them. The three books read similarly enough, thematically; at the same time, each author’s style is so distinct, they stand on their own.

Oates’ opening story, “Nearby, the Edge of Europe,” is about a college professor’s trip to Ireland with his family. Martin, our protagonist, traveled to these same parts as a boy, only to see tragedy befall his extended family while there. Now, he’s back with Caitlin—his famous novelist wife—and their three kids, trying to save his marriage. Caitlin, by the way, doesn’t want to be there, on top of the fact she’s started drinking heavily in the past couple of years. The family stays with Martin’s cousins, the same cousins he stayed with as a boy, and Martin must not only face the reality of his marriage, but an old relative to whom that tragedy befell.

“Looking for Service” is about an unnamed guy who journeys somewhere down to South America. He’s an accountant for a major mining corporation and his job is to travel to foreign branches and be the bad guy, look over their books and make sure they’re doing what they say they’re doing. While on his current trip, he runs into a young American couple, idealists who take to him like strays dogs, full of pep and looking for handouts. Their idealism eventually gets the best of them, however, and our guy’s stuck in the middle of it all.

“The Yellow House” is a shorter piece, the shortest in the book, and is about a guy who spies a particular yellow house on his way to and from work every day from his train window. The house makes him think of the house he lived in as a kid, the story sending its protagonist on a journey of a different kind.

That brings us to the title story, “The Empty House,” the last story in the book and my favorite of those I’ve read. “The Empty House” is a split point-of-view story, firstly about Ryan, an American journalist set to meet an old college friend, now a missionary in Guatemala. Ryan has been working in Chile and Argentina, writing about political uprisings and such, and has perhaps pressed the wrong buttons with the wrong government officials. He’s on his way home when he stops in Guatemala to see his friend.

At this point, the story cuts over to Ryan’s younger brother, a decade and a half later (and switches from third to first person at the same time). Ryan has been missing for years, since the proceedings of Ryan’s half of the story, and his brother, now in his twenties, has come to Guatemala in search of answers. He wants to at least talk to someone about the case, or perhaps merely to retrace his brother’s last-known steps. The civil war has recently ended, but this unnamed brother is still a stranger in a strange land, and there’s definitely still danger about, especially for a lone American asking too many questions about long-past disappearances.

The story follows this pattern, Oates shifting back and forth between timelines and brothers. Ryan wades deeper into his investigation. His priest friend never meets him at the train station, and after some looking around, Ryan finds his body in the courtyard of his parish, badly beaten and malformed. Ryan’s work—for which this Guatemala story was always just an extra—takes a backseat: He now just wants to get back to the States. He isn’t sure who to trust or how to even arrrive safely at the airport, however, his plane just a day away.

The brother’s story, which is given fewer words, keeps on Ryan’s trail, but sadly, there’s not much to go on: The details surrounding Ryan’s disappearance are slight. He can’t even find a case file at any police station.

Eventually, Oates reveals why this is, solving the mystery of what happened to Ryan, why he never returned to America, why his brother had to come looking for him fifteen years later. I won’t reveal that here, though, as that would be too much. “The Empty House” is a really well told tale, cleverly structured, key details revealed at the exact right moment, yet snaring us into the narrative early with the right details. This, mixed with Oates’ keen sense for his settings, rings a true, exciting tone. It’s no wonder this story ended up in the Best American Mystery Stories anthology, a whodunnit, or perhaps a whuthappind.

I thoroughly enjoyed Nathan Oates’ debut collection, The Empty House. Ficton is all about giving characters problems to deal with, only some authors handle that better, and more uniquely, than others. I liked reading about these characters’ issues, set amidst these unfamiliar (to me) landscapes. Oates weaves conflict and setting so seamlessly, I wonder if he hasn’t been to all these places, hasn’t experienced all these events. He’s is a skilled writer and I’m thrilled to have spent this time with his earlier work today.